Ultimate Guide to Phone Readiness for Kids (Ages 9–12)

Giving your child their first phone is a major parenting milestone in the digital age. Many parents of 9–12-year-olds ask the big question: “Is my child ready for a phone?” The answer isn’t simply about age – it’s about maturity, responsibility, and preparation. In this guide, we’ll define “phone readiness,” help you gauge the right age, and provide concrete checklists, signs, skills, and steps to ensure your child’s first phone experience is positive and safe.

Is My Child Ready for a Phone?

In short: A child is ready for a phone not when they reach a certain birthday, but when they show enough emotional, social, and digital maturity to handle the responsibility. This means they can follow rules without constant supervision, respect boundaries, and navigate online spaces safely. Below is a quick checklist to help you decide if your 9–12-year-old is ready.

Quick Answer – Phone Readiness Checklist: Ask yourself if your child…

- Handles responsibilities (homework, chores) reliably without constant reminders.

- Shows impulse control, like pausing to think before acting or posting.

- Understands privacy and safety – knows not to share personal info or talk to strangers online.

- Communicates openly with you about their day and feelings (likely to tell you if something online bothers them).

- Follows screen time limits on games/TV without meltdown and can put devices down when asked.

- Handles peer pressure – isn’t swayed to do things just because “everyone else is”.

- Has a real need for a phone, like safety during solo commutes or coordinating pick-ups (as opposed to just FOMO).

- Understands consequences – realizes that texts and social posts are permanent and public.

- Demonstrates emotional maturity – can cope with minor frustrations or conflicts without dramatic outbursts.

- Accepts family tech rules – willing to follow rules about when/where the phone can be used (e.g. no phone at bedtime).

If you checked most of these, your child may be ready. If not, they likely need more time, guidance, and skill-building before a smartphone.

What Does “Phone Readiness” Mean? (Emotional, Social, and Digital Maturity)

“Phone readiness” isn’t a formal term you’ll find in a textbook, but it boils down to being prepared in three areas: emotional maturity, social maturity, and digital savvy. Here’s what that means:

- Emotional maturity: Does your child have the impulse control and self-discipline to use a phone responsibly? For example, can they pause and think before reacting to a text or post? A ready child can manage their feelings when the phone pings or when they see something upsetting online, rather than acting out. Kids who tend to act before thinking or get easily upset by social drama may need more time. Emotional maturity also means handling the potential distractions of a phone – like knowing to put it down during homework, family meals, or bedtime.

- Social maturity: A phone opens the door to communication with friends (and strangers). Is your child socially aware enough to use this tool kindly and safely? Socially mature kids understand respect and empathy – they know that if it’s not okay to say something in person, it’s not okay online. They can handle peer pressure and bullying appropriately (e.g. not joining in hurtful messages, and telling an adult if they witness cyberbullying). They also respect others’ privacy and boundaries, and understand that what they share can affect their and others’ reputations.

- Digital maturity: This includes basic digital literacy and safety skills. A “digitally ready” child knows fundamental rules like never sharing personal information or passwords online, not clicking suspicious links, and recognizing a scam or dangerous situation on the internet. They grasp that the internet has real-world consequences – for instance, that messages and photos can be saved or forwarded (nothing truly “disappears”). They should also be able to do simple troubleshooting and understand the limits you set on the device. Essentially, they have the know-how to protect themselves and the judgment to “spot” red flags online.

Phone readiness is all three of those areas coming together. It’s normal for a 9–12 year old to be stronger in some areas than others. Your role is to gauge where your child stands and help them build up any weak spots (through practice and guidance) before handing over a smartphone. In the next sections, we’ll talk about age expectations, clear signs of readiness (and non-readiness), critical skills to teach, and how to prepare your child for that first phone.

What Age Should a Child Get a Phone?

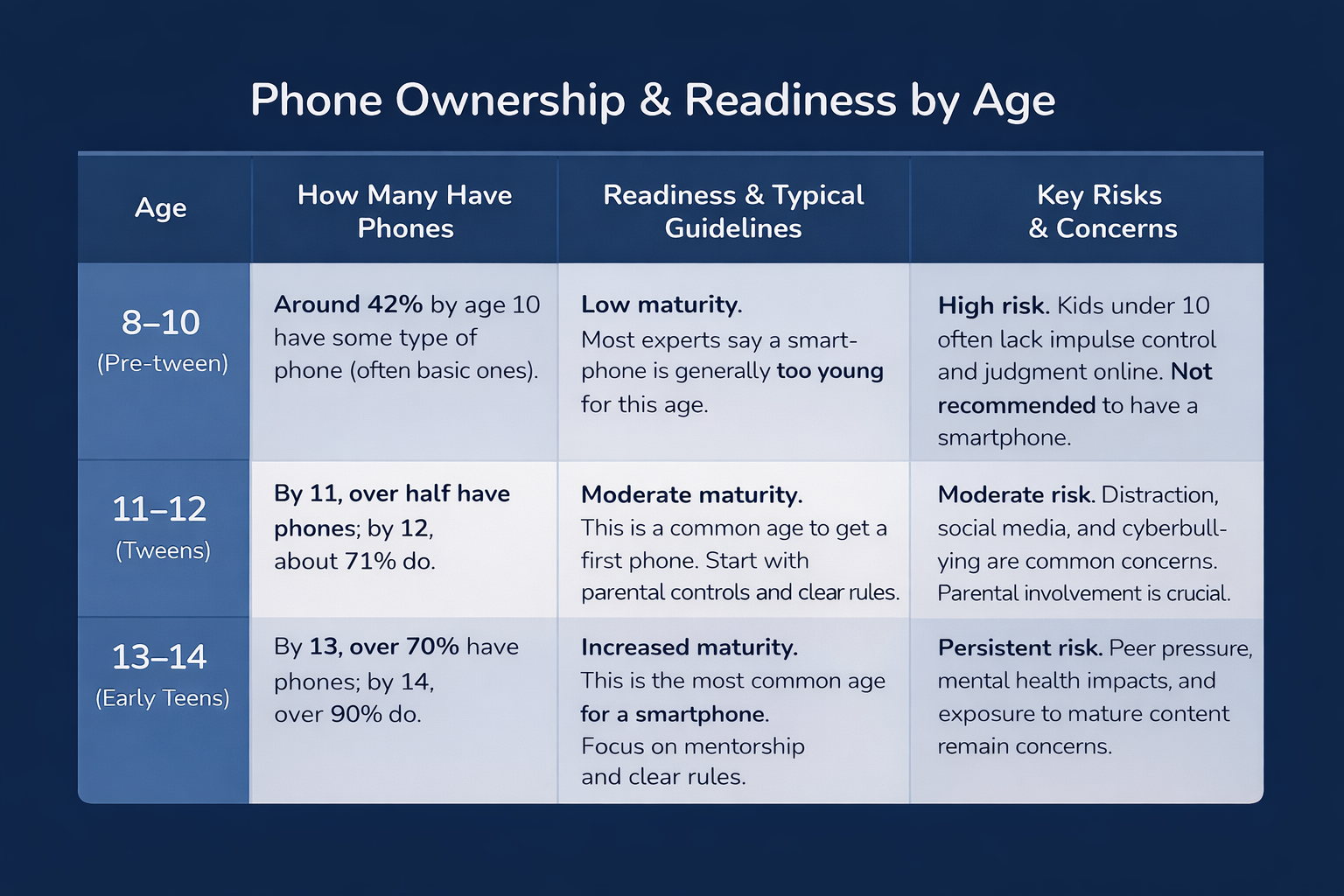

Parents often ask, “At what age do most kids get phones?” or “Is there a ‘right’ age for a first phone?” There is no magic number that fits every child. Developmental experts generally suggest waiting until at least early adolescence (around 12–14 years old) for a full-access smartphone, but some kids may be ready earlier and others later. In practice, many American kids do get phones in the tween years: the average age for a first smartphone in the U.S. is around 10 years old. By age 12, about 71% of kids have some type of phone, and by 14 it’s 91%.

That said, age alone doesn’t determine readiness. It’s crucial to weigh your child’s maturity and your family’s needs. To help illustrate, here’s a comparison of readiness and risks by age group:

Remember: Every child is different. Some 10-year-olds might handle a phone better than a 15-year-old, depending on personality and guidance. Use age as a rough guide, but ultimately base your decision on your child’s readiness and your family’s situation. For example, a child with a long school commute or in a split-household might get a phone earlier out of necessity, whereas a child who is socially immature might benefit from waiting longer.

If you decide your child is not ready yet, that’s okay! It’s far better to wait than to rush it. (We’ll discuss alternatives and how to handle “not yet” a bit later in the FAQ.) The key is that whenever the age you choose – be it 11, 13, or 15 – you prepare your child with the right skills and support beforehand.

10 Signs Your Child Is Ready (Or Not Ready) for a Phone

How can you tell, in practical terms, if your child is truly ready for that responsibility? Here are ten telltale signs to look for – five positive signs of readiness and five warning signs that they might not be ready yet. Use these as a guide alongside your parental intuition:

5 Signs Your Child Is Ready for a Phone

- They demonstrate responsibility in daily life. Does your child complete homework and chores reliably and take care of their belongings? If they can keep track of a backpack or jacket without losing it every week, that’s a good indicator they may handle a phone responsibly. Responsible behavior in other areas (like following house rules and meeting obligations) often translates into responsible tech use.

- They have good impulse control. A ready child can “pause” before acting – for example, they won’t send a nasty text out of anger or click every pop-up they see. If your kid can resist the urge to, say, eat candy before dinner or binge TV past bedtime (most of the time!), they might also resist the constant temptations of a smartphone. On the other hand, if they often act without thinking or need you to constantly police their behavior, they may struggle with an always-available phone. The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests assessing whether your child “tends to act before thinking” or has solid impulse control when considering phone readiness.

- They communicate openly with you. One of the biggest safety factors is whether your child will tell you if something’s wrong. Ready kids will come to you if they encounter a disturbing video, receive a mean comment, or get a text from a stranger. There’s a foundation of trust and open conversation. For instance, will your child admit if they saw an inappropriate website, or would they hide it? If they already talk to you about their friends, feelings, and problems, that’s a great sign. “The smartphone conversation is really about trust and communication, not technology,” notes one digital parenting guide. If your child is very secretive or fearful of coming to you when things go wrong, you’ll want to improve that openness before they get a phone.

- They understand personal boundaries and safety. Quiz your child on some hypothetical scenarios: What would you do if a stranger messaged you online? Is it okay to share your address or school on an app? A child who is ready for a phone can answer these in a safe way – e.g. “I’d not respond and tell an adult” or “Never share personal info”. They should know basic online safety rules by heart. Also, a ready child respects real-world boundaries: they ask permission before taking or sharing someone’s photo, they know not to text or call people at inappropriate times, etc. If your kid already practices good privacy habits on a family computer or tablet, that’s a strong readiness sign.

- They handle screen time and internet use responsibly. Think about how your child manages the technology they already have (TV, tablet, gaming console, etc.). Do they follow the time limits you set without constant tantrums? Do they make an effort to turn off devices at bedtime or come to the dinner table without a fuss? A child who can self-regulate their screen time – even just a little – is more likely to use a phone within healthy boundaries. Also, consider their exposure to digital content so far: have they engaged with age-appropriate content and reacted appropriately? If they’ve “healthfully and safely engaged with digital media in the past” (for example, using a school tablet or watching YouTube Kids without issues), that’s a positive sign.

5 Signs Your Child is Not Ready Yet

- Frequent rule-breaking or irresponsibility. If your child struggles to follow basic rules at home or school, adding a smartphone to the mix could make things worse. Signs of not-ready: they frequently lose or break things, ignore chores/homework until you nag, or can’t stick to limits (like sneaking extra screen time). If they can’t keep track of their shoes or remember simple rules, they’re likely not ready to manage a device that offers endless entertainment and distractions.

- Poor impulse control or emotional outbursts. Pay attention to how your child behaves when frustrated or tempted. Do they melt down if you take away the iPad, send angry messages in the heat of the moment, or make reckless choices like clicking on sketchy links? If so, handing them a smartphone (which is basically a tiny, powerful computer) might be risky. A phone gives instant gratification and anonymous communication – a bad combo for a child who hasn’t developed self-control. As one pediatric psychologist puts it, if a child has “self-regulation difficulties that a smartphone might worsen,” it’s a sign to wait.

- Secrecy or dishonesty about technology use. If your child is already using devices (like a tablet or family computer) and you catch them hiding their screen, lying about what they’re doing, or creating accounts behind your back, that’s a red flag. A not-ready child might view a phone as a way to escape parental oversight entirely. Trust is critical – if it’s not there yet, hold off. It’s better to delay a phone than to give one to a child who isn’t ready to use it under your guidance.

- Heavy peer pressure focus (“But everyone else has one!”). Nearly every tween will say “everyone else has a phone.” But if the only reason your child wants a phone is to fit in or because of social media envy, that’s not a sign of true readiness – it’s a sign to have a conversation. A child who is not ready may be fixated on the glamour of having a phone (games, social apps, status) without understanding the responsibility side. Be wary if your 9–12-year-old is more interested in Snapchat and TikTok than in staying connected with family. That mindset can lead to trouble, especially if they’re willing to break age rules (like lying about being 13 to get on social media).

- Lack of understanding of consequences. Ask your child what could go wrong with a phone. Do they shrug, or do they mention things like cyberbullying, spending too much time online, or privacy risks? If they don’t grasp the consequences, they’re not ready to navigate them. For instance, a not-ready child might think that deleting a message makes it gone forever (not realizing others can screenshot it). Or they might not connect late-night phone use with being tired next day. If cause-and-effect thinking isn’t there yet, give it time and education. You want them to understand, for example, that hurtful messages can deeply affect someone or that certain posts can get you in trouble at school or even legally. Without this understanding, they could easily make mistakes that have lasting impact.

If you recognize several of these “not ready” signs, don’t panic – it doesn’t mean your child will never be ready. It just means you should hold off on the smartphone for now. Use the time to address the issues: set firmer limits, teach about online safety, or maybe give them smaller responsibilities to build trust. (You can also use a formal readiness quiz or tool; for example, the American Academy of Pediatrics worked with AT&T to create a 10-question PhoneReady Questionnaire that helps gauge if a child is “Ready,” “Almost Ready,” or “Not Yet Ready” for a phone.)

Above all, be honest with your child. If you decide to say “not yet,” explain that it’s not a no forever – it’s an invitation to work on skills and habits so they can earn that privilege. In the meantime, you might find compromise solutions like a basic phone or shared family device, which we’ll discuss below.

4 Critical Skills Every Child Needs Before Their First Phone

Before you hand over that first phone, it’s wise to coach your child in a core set of digital skills. Think of it as “digital citizenship” training or a beginner’s license for phone ownership. We can sum these up as the ability to: Pause, Protect, Spot, and Decide. Make sure your child can do each of the following:

- Pause: The skill of self-control and think-before-you-act. Teach your child to pause before reacting or posting. For example, if they draft an angry text or feel excited to share a silly photo, have them stop and review it first: “Is this something I’ll feel good about later? Would I say this in person?” This pause can prevent a lot of mistakes. The FTC’s advice for teens is spot on: before you send a message, ask yourself, “How will this make other people feel? How would I feel if it was shared around?”. Whether it’s a text, a social post, or replying to someone online, a child should learn to take that breath and make sure they won’t regret their action. Impulse control is like a muscle – practice it in small ways (like not answering a notification immediately) to build the habit.

- Protect: The skill of staying safe and protecting privacy. Your child should know how to protect both the device and their personal information. This includes using strong passcodes and not sharing them, locking the phone when not in use, and never giving away personal details (name, address, school, photos, etc.) to strangers online. Teach them about privacy settings too – for any app or game, there will be settings to limit who sees their profile or how to block unknown contacts. A phone-ready kid should be able to follow the rule “never post or send anything you wouldn’t want the whole school to see.” Emphasize that once something is out there, you can’t take it back. They should also understand not to meet up with online “friends” in real life and how to tell a trusted adult if anyone makes them uncomfortable. In short, “Protect” means they know how to use the phone as a safety tool (to contact you in emergencies) without exposing themselves to unnecessary risks.

- Spot: The skill of recognizing red flags online. Scammers, predators, cyberbullies – unfortunately these exist even in kid-friendly spaces. Before getting a phone, your child should practice how to spot scams and harmful behavior. Go over common red flags: if someone you don’t know messages you – don’t reply. If an offer or link sounds too good to be true – don’t click it. The FTC recommends teaching kids to watch for things like messages from strangers, bad grammar or sketchy links, and to never give out family info in response to an unsolicited message. Similarly, kids should learn to recognize cyberbullying or creepy behavior (like an online stranger asking weird questions) as red flags. Role-play a few scenarios: “What if someone you met in a game asks for your photo?” “What if you get a text that you won a free prize?” Ensure they know the correct response (ignore, block, tell an adult, etc.). We want them to have their “radar” up when navigating the online world.

- Decide: The skill of making wise decisions (especially when no adult is around). This is the culmination of the above skills – knowing how to act responsibly when faced with choices on their phone. We won’t be hovering over their shoulder 24/7, so they need the tools to decide on their own: Should I respond to this message? Is it okay to download this app? It’s bedtime – do I turn off the phone? A phone-ready child has a sense of right and wrong in the digital context and can apply it. They should also know when not to decide alone – i.e. when to ask for help. If something happens that they’re unsure about (like they saw something disturbing or a friend is acting weird online), the decision should be to involve a parent or trusted adult. Experts call this building an “internal filter” or digital resilience. One tech parenting expert put it this way: our goal is to teach kids “how to behave when we are not in the room…empowering them to make smart decisions” on their own. Start giving your child small decisions now (like managing a small budget in an app, or choosing which friend group chat to join) and coach them through the outcomes. This will build their decision-making muscle for bigger issues later.

Each of these skills can be taught and practiced even before your child has a personal phone. In fact, it’s much better to practice first (on family devices or in hypothetical situations) than to hand over a phone and hope they figure it out. If your child can Pause, Protect, Spot, and Decide well, they’re not just ready for a phone – they’re ready to use it in a healthy, positive way. These skills turn the phone from a risky gadget into a powerful tool for growth and connection.

Why Parental Controls Aren’t Enough (Build Competence, Not Just Controls)

Modern phones offer a lot of parental control features: app blockers, web filters, screen time limits, GPS trackers, you name it. These are useful tools, and you should absolutely use appropriate controls (especially at the start). But here’s a critical truth: parental controls alone are not sufficient to keep your child safe in the long run. Relying solely on locking down a phone is a bit of a false sense of security – digital experts warn that tech-savvy kids “can’t just be fenced in”. As one child safety advocate bluntly says, “They’re not perfect – children can bypass them if they’re clever enough.” In other words, any filter or limit you set can eventually be figured out or worked around by a determined tween. Kids often share tips with each other on how to get past WiFi restrictions or sneak in screen time (sometimes making parents feel like it’s a game of whack-a-mole).

Furthermore, no combination of settings can cover every scenario. Even if you lock down your child’s own phone, they might use a friend’s device or a school computer without those controls. Or they might encounter mature content in a seemingly safe app. Reality: your child will inevitably be exposed to the wider internet and all its pros and cons, controls or not. That’s why digital competence and character matter more than any app setting.

Consider parental controls as training wheels – they help support safe usage while your child learns the rules. But the ultimate goal is for your child to know how to ride on their own. “These tools are a mere step in a far more nuanced process which comes down to conversation and communication,” notes Luke Savage of the NSPCC (a child safety organization). In practice, this means continuously talking with your child about what they see and do online, and guiding them on how to respond. For example, no filter is 100% – so if your child does come across something inappropriate or gets a suspicious message, will they know what to do? That comes from education and ongoing dialogue, not just an app.

Another reason not to over-rely on controls: overly strict surveillance without trust-building can backfire. Kids might feel “spied on” and become more secretive, or they might never learn to self-regulate because an app was always doing it for them. Many parenting experts instead recommend a mentorship approach: yes, use controls, but also spend time mentoring your child in responsible use. “It’s not about controlling our children, and it’s not about fear,” says digital parenting coach Elizabeth Milovidov. “It is about empowering them to make smart decisions… teaching them how to behave when we are not looking over their shoulder.” This empowerment only happens through practice and trust, not just through a locked-down phone.

Finally, surveys show not all parents even use parental control tools – and those who do still worry. Roughly half of U.S. parents say they have used parental controls on their kids’ devices, yet a majority also believe smartphones can be harmful to kids’ wellbeing if not managed properly. The take-home point is: technology tools can help, but they don’t replace parenting. Make sure you actively engage with your child’s digital life. Ask about their favorite apps, play a mobile game together, check their texts occasionally (with their knowledge), and keep the dialogue open. If something concerning slips past the filters – and at some point, it will – your child should feel comfortable coming to you for help.

In summary: Use parental controls as a supportive layer of safety, but don’t let them be your only strategy. Your end goal is a young person who is competent and confident in navigating the digital world, not one who only stays safe because you had every website blocked. It’s the internal controls (judgment, values, and habits) that will ultimately keep your child safe when they’re an independent teen and beyond.

How to Prepare Your Child Before Giving Them a Phone

Simply deciding your child is “ready” isn’t the end of the journey – it’s the beginning. Preparation is key to a successful first phone experience. Think of it this way: you wouldn’t hand a teenager car keys without some driving lessons and a learner’s permit phase. Similarly, a child shouldn’t jump into smartphone ownership without training and a gradual introduction. In this section, we lay out a practical step-by-step checklist to prepare your child for their first phone.

1. Start with a discussion (and keep talking).

Begin by having a frank conversation with your child about why you’re considering giving them a phone and what responsibilities come with it. This is not a one-time lecture, but the start of an ongoing dialogue. Make your expectations clear and also listen to your child’s thoughts. Why do they want a phone? What do they think owning one will be like? Use this talk to gauge their understanding and to set a positive tone: you’re entrusting them with a tool, and you believe they can rise to the challenge if they follow the agreed rules.

Together, draft a family phone agreement or contract – essentially a list of rules and responsibilities that you both sign off on. Writing it down makes it concrete. Include points like: when and where the phone can be used (e.g. “No phones during meals or after 9PM”), keeping passwords known to parents, not deleting message history, not using the phone to hurt others, etc.. Also state consequences for breaking the rules (such as loss of phone privileges for a day). This agreement isn’t just about enforcement; it’s a tool to discuss values and safety. While drafting it, talk about topics like digital citizenship (being kind online), what to do if they see something upsetting, and how to balance phone time with other activities.

Importantly, make the conversation two-way. Encourage your child to ask questions and voice concerns. If they feel involved in setting the rules, they’re more likely to follow them. Keep these dialogues going even after they get the phone – maybe a weekly check-in about how things are going, what new apps or games they’re into, any issues that arose, etc. This ongoing mentorship approach will help them feel supported. Remember, communication is your best tool; as one expert says, “as long as you’re talking to them” consistently, you can guide them through whatever comes up.

2. Choose the right first device (it doesn’t have to be a full smartphone).

“Smartphone” covers a lot of ground – from a basic phone that just calls and texts, up to an iPhone 15 loaded with social media. You have options in what kind of device to give as a “starter” phone. In many cases, a scaled-down device is better for beginners. For example:

- Flip phone or basic phone: These devices can call and text but have no internet, no app store. They’re great purely for communication and safety. Organizations like the Wait Until 8th movement advise parents to consider basic phones or watches as an interim step. Even the AAP suggests alternatives like “a flip phone or watch that allows communication without all the digital baggage” for younger kids. Your child can learn calling and texting etiquette without the risk of social media or YouTube temptations.

- Smartwatch for kids: Kids’ smartwatches (or a pared-down smartwatch from your carrier) often allow preset contacts, GPS tracking, and maybe voice messages, but no open internet. This can be perfect for a 9–10 year old who needs to call home after school but isn’t ready for Instagram or unsupervised browsing. It’s essentially a phone on training wheels – they can contact you, but can’t get into too much trouble online.

- Old smartphone with no data plan: Another idea is to give them an old smartphone without cellular service, so it only works on Wi-Fi. This way they can use it at home or in supervised settings to play games or music, but they can’t use it freely outside (where there’s no Wi-Fi). This lets them practice handling a device – keeping it charged, not dropping it, using apps responsibly – before they have 24/7 mobile internet access.

There’s nothing wrong with delaying the “fully loaded smartphone” until they’ve shown readiness with these simpler devices. Many families take a gradual approach: maybe start with a smartwatch at 10, then a talk-and-text phone at 11, and only at 13 give a true smartphone. Each step builds digital skills and trust. So, think creatively about the device itself. The latest iPhone is not a requirement for childhood! The best first phone might be something that meets the communication need (stay in touch with family, coordinate pickups) without exposing your child to the full smorgasbord of apps and internet content on day one.

3. Set it up together with safety in mind.

Once you’ve picked the device, don’t just hand it over right out of the box. Do the initial setup together, making use of all those parental controls and safety features from the start. Think of this as “customizing” the phone to your family’s rules. Here’s a checklist of setup steps:

- Install parental control tools and monitoring: Enable the phone’s built-in parental controls (like Apple Screen Time or Google Family Link) or a trusted third-party app. During setup, you might restrict app downloads, set age filters for content, and impose daily screen time limits. For example, you can whitelist certain apps and block app store purchases, require permission for new app installs, turn on explicit content filters, etc.. Do this immediately – “Don’t wait to see how it goes”, as one tech guide advises. You can always loosen restrictions later if things go well, but it’s harder to tighten them after the fact.

- Configure privacy and security settings: Go through each app or feature on the phone and adjust privacy settings. Disable location sharing on social apps, limit who can see their profiles, and turn off any public features. Set messaging or chat apps to “friends only” if possible. Make sure the phone itself has a strong passcode that you both know. Explain to your child why these settings matter (e.g. “We’re keeping your account private so only people you know can see you”). Encourage them to value their privacy and security from day one.

- Add essential contacts and info: Pre-program important numbers (parents, relatives, emergency contacts) into the phone. Also, show them how to use the emergency call feature. If the phone has an ICE (in case of emergency) contact or medical info section, fill that out together. This reinforces that the phone is first and foremost a safety tool to reach trusted people when needed.

- Delay or disable social media: For a first phone, it’s wise to hold off on social media apps. Most are 13+ by terms of service anyway. Even if your child is 13, consider delaying those a bit longer until they’ve shown they can handle texting and regular internet use responsibly. If the phone comes with any pre-installed social media or browser that you’re not comfortable with, remove or restrict it initially. You might tell your child, “We’ll start with just texting, camera, and a few fun apps, and we’ll consider Instagram or TikTok when you’re a bit older.” This can prevent a lot of potential issues in the early stages (social media is often where tweens get into comparisons, drama, inappropriate content, etc.). One step at a time.

Taking these steps together is important. By involving your child in the setup, you’re teaching them as you go. Explain each setting (“We’re turning on YouTube restricted mode so you don’t accidentally see adult videos”). When kids understand the “why” behind a rule or control, they’re more likely to follow it. As AAP recommends, “set these up together with your child, and explain the reasons behind the limits and controls”. This transforms parental controls from feeling like a prison into feeling like a family safety plan.

4. Phase it in – use a gradual “trial period.”

The first few weeks with a phone are a learning period for both child and parent. It helps to treat it as a trial run or as if your child is on a “learner’s permit.” You might explicitly tell them, “Let’s try this phone out for a month with these rules, and we’ll review how it’s going.” Here are some ways to phase in privileges over time:

- Start with limited access: In week one, you might allow only core functions – calling and texting with family and close friends, a camera, perhaps a music or drawing app. No web browser or social media yet. Keep the app selection minimal. This reduces overwhelm and lets them master basics like good texting etiquette. Also consider a “phone curfew” from day one: at night, the phone stays in a central charging spot (not the bedroom) – this prevents late-night use and establishes healthy boundaries early.

- Conduct frequent check-ins: For the initial month, check the phone daily or several times a week. This isn’t snooping; it’s mentoring. Let your child know you’ll be checking their messages and apps “just to make sure everything’s okay.” When you do a check, use it as a teaching moment: praise them if they handled something well (“I like how you ended the game chat when people started arguing – that was smart”), or gently correct if needed (“I noticed that group chat had some mean jokes – how did you feel about that? Remember, you can always exit a chat if it gets nasty.”). Maintaining openness is key so they don’t feel the need to hide things.

- Gradually add freedoms: If after a few weeks your child is following rules and showing responsibility, you can slowly grant more access. For example, after two weeks of good behavior, maybe allow a vetted app they’ve been asking for (like a kids’ game or messaging app with parent oversight). After a month or two, if all is well, you could extend their daily screen time or allow the phone to stay with them later in the evening. Each new privilege should come with a conversation about how to handle it. “Okay, you can use Safari now, but let’s talk about what sites are off-limits and what you’ll do if you accidentally land on a bad site.” Essentially, “unlock” new features as they earn trust. This shows your child that responsible use leads to more freedom, which is a powerful lesson in itself.

- Keep some guardrails long-term: Gradual phasing in doesn’t mean you remove all limits eventually. Some rules should remain firm (for example, no devices after a certain hour for healthy sleep, or you must approve any new contacts they add). But as your child proves they’re trustworthy, you might move from heavy monitoring to spot-checks. By the time they’re a bit older, you ideally transition into a role where they manage most of their phone use autonomously, with you available for help and regularly checking in through conversation rather than constant surveillance.

One approach many families find helpful is to frame the first phone as an experiment, not a permanent entitlement. The AAP suggests, “Treat getting a phone like an experiment. As your child shows more responsibility, they gain more independence and fewer controls.” If the experiment isn’t working (e.g. grades are slipping or rules are being broken), it’s okay to scale back the privileges or even take a step back from the phone for a while. You’re not “failing” – you’re adjusting the learning process.

Tip: Some parents implement a “30-Day Phone Launch Plan”, which breaks this trial period into structured weeks. We’ve provided a sample plan below that you can adapt.

Sample 30-Day Phone Launch Plan

(Feel free to adjust based on your child’s maturity and your schedule. The idea is to go from highly structured to gradually more independent over one month.)

- Week 1 (Days 1–7): Orientation and Rules – For the first week, the phone is in “training mode.” Go over the phone’s functions together. Each day, introduce a new concept (Day 1: how to call/text; Day 2: how to use the camera respectfully; Day 3: messaging etiquette; etc.). Keep usage short and supervised. For instance, the child can use the phone for 30 minutes after school in the living room where you can see them. Establish the habit of charging the phone overnight in a parent’s bedroom or common area from day one. At the end of Week 1, sit down and discuss: What did they enjoy? Any questions or mistakes? Reinforce the positives and clarify any misunderstandings.

- Week 2 (Days 8–14): Limited Independence – Now the child can carry the phone to school or activities if needed, but with tight rules. Perhaps they can text a couple of friends under your guidance. Introduce one new app or feature this week (maybe a fun game or music app you approve). Observe how they manage it. Continue daily check-ins of messages and usage logs. This is the week to role-play any scenarios they might encounter (spam calls, a mean text from a friend, etc.): “Remember what we do if you get a text from an unknown number…” Encourage them to start self-monitoring: for example, ask “Did you remember to put it on the charger by 8 PM?” so they start taking ownership.

- Week 3 (Days 15–21): More Features, Same Oversight – If things are going well, you can enable another feature like the web browser with filters, or allow a longer usage window (say, a bit of phone time after homework is done). By now the novelty may be wearing off, which is good – they’re integrating the phone into normal life. This week, maybe don’t check the phone every single day; move to every other day, and see if they still behave knowing you might check at any time. It builds a bit of self-accountability. Continue to enforce core rules (no phones at night, etc.) consistently. If any rule is broken (they played a game during homework, for example), enforce the agreed consequence calmly and reset expectations.

- Week 4 (Days 22–30): Evaluation and Adjustment – By the fourth week, you and your child have a month of experience to look at. Have an honest review meeting: How do you feel you’ve handled the phone? Is it hard to follow the rules? What can we do better? Share your perspective too – praise their successes (“You’ve been very good at not answering during homework, great job!”) and note any concerns (“I noticed a couple times you tried to sneak it after lights out – we need to work on that”). This is a good time to adjust the plan: maybe they’ve earned a little more freedom in one area, but need more supervision in another. Update your phone agreement if needed. Crucially, make sure your child understands this plan is ongoing – even after 30 days, you’ll still have limits and check-ins, but if they keep doing well, they’ll get more privileges. Conversely, if problems persist, you might extend the “training” period or take a break from phone ownership and try again later.

The goal of a launch plan is to establish healthy habits and trust early on. It’s much easier to start strict and gradually loosen up than to start lenient and try to rein things in after problems arise. By the end of a successful first month, your child should understand that having a phone is a conditional privilege – one that comes with responsibility and can be adjusted if misused. Ideally, they’ll also appreciate that you’re involved not to snoop or punish, but to help them learn. One parent compared it to teaching a kid to drive: “You don’t hand over the keys to a sports car and say ‘figure it out.’ You start in a parking lot, then quiet streets, then highways. Same deal here.”

Throughout this process, keep reinforcing core values: kindness, balance, safety, and honesty. And remember to model good behavior yourself – if you preach “no phones at dinner” but sneak a glance at yours, the lesson won’t stick. Show them what responsible phone use looks like in your own habits. Kids learn a ton by watching.

By investing time and effort into preparation, you are setting your child up for success. It may feel like a lot of work upfront (and it is!), but the payoff is a child who is far less likely to fall into the common pits of phone trouble. Instead of being overwhelmed or making dangerous mistakes, they’ll gradually become a savvy, respectful, and confident phone user. That foundation will serve them for life.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Finally, let’s address some common questions parents ask about kids and first phones. These quick Q&As summarize key points from our guide and provide additional insights for high-intent queries.

Q1: What is the right age for a child to get a smartphone?

There is no single “right” age – it depends on the individual child’s maturity and your family’s needs. Most experts recommend waiting until at least early adolescence (around 13–14 years old) for a full-featured smartphone. In practice, many kids get phones earlier: surveys show about 42% of kids have a phone by age 10, 71% by age 12 and most (91%) have one by 14. The average age to get a first smartphone in the U.S. is around 10 years old, but that doesn’t mean 10 is right for everyone. It’s crucial to consider your child’s maturity, responsibility level, and actual need for a phone. For example, a 12-year-old who walks home alone and shows good judgment might be ready, whereas a 12-year-old who is very impulsive or never away from adults might not be. Bottom line: Don’t fixate on a number. Use age as a guideline, but make the decision based on readiness (see the checklist and signs above) and whether you as a parent are ready to actively supervise the phone use. If in doubt, err on the side of waiting – there’s little harm in waiting a bit longer, but potentially lots of harm in giving a phone too early.

Q2: How can I tell if my child is ready for a smartphone?

Look for signs of readiness in their behavior and attitude. Key indicators include showing responsibility (they follow rules and take care of things), having good self-control (they can handle screen limits and emotional ups and downs), understanding safety rules (like not talking to strangers online), and being open with you (they’ll come to you with problems). Our guide above lists 10 signs your child is ready or not ready – using those can help you gauge. You can also use formal tools like the AAP’s PhoneReady Questionnaire, a 10-question quiz that gives a recommendation of “ready, almost ready, or not yet” based on your child’s maturity and your values. If your child passes most of the readiness criteria and you are prepared to guide them, they’re likely ready. If they exhibit several “not ready” signs (impulsiveness, lying, unmanaged screen use, etc.), then it’s wise to hold off. Remember, readiness isn’t all-or-nothing; you can work on weak areas and revisit the decision in a few months. When in doubt, do a trial run (like a limited-use device) to test their readiness in a controlled way.

Q3: What if my child isn’t ready for a phone yet, but they keep asking?

It’s perfectly okay to say “Not yet.” In fact, it’s far better to delay than to give in too early. Explain to your child that a smartphone is a big responsibility and that you’re waiting until they’re truly ready. Emphasize that this is about safety and success – you want their first phone experience to be positive, not harmful or stressful for them. You can also highlight that many parents feel the same; movements like “Wait Until 8th” encourage waiting until at least 8th grade for smartphones, and thousands of families choose to delay. To make the wait easier, offer alternatives to meet their needs: if the main issue is contacting friends, maybe let them use a shared family phone or a simple flip phone to call/text. If they want games, allow some on a tablet or computer with supervision. If it’s about social connection, arrange more in-person hangouts or let them use messaging on your device at certain times. HealthyChildren.org (AAP) suggests exploring non-smartphone options that still meet social needs – for example, enabling text and video chat on a home tablet instead of giving a personal phone. You can also involve them in ongoing learning: “We’ll get there. Let’s keep working on showing you’re ready – maybe in a few months we’ll try again.” Revisit the conversation periodically. As they mature, they’ll likely start to meet the criteria and you can reconsider. The key is to make this an ongoing dialogue, not a one-time “no.” Let them know you understand it’s hard to wait, but you’re doing it because you care. By framing it as “we’re preparing you for this big step” rather than just denying them, you’ll get more buy-in. And yes, they might say “you’re the only parent who won’t allow it,” but stand firm – you are allowed to be the parent, even if it’s unpopular. Childhood moves fast, and a little more time without a smartphone can be a good thing for their development.

Q4: How can I keep my child safe when they do get a phone?

Keeping a child safe with a phone involves a combination of technology tools, clear rules, and ongoing guidance. Here are the essentials:

- Set up parental controls and limits: Use the phone’s parental control settings or a dedicated app to filter content, set screen time limits, and manage app downloads. For example, you might disable in-app purchases, limit mature websites, and cap daily usage time. These controls act as a safety net to prevent a lot of common dangers (like stumbling onto adult content or spending $100 in an app). Just remember, these are not foolproof, so they’re one layer of safety, not the only one.

- Establish rules and a contract: As discussed, create a family phone contract outlining rules (no phones during homework, no secret passwords, no bullying, etc.). Be explicit about safety rules, like never sharing personal info or meeting online “friends” in person. Also cover etiquette: how to respectfully communicate and not overshare. Set consequences so they know what happens if rules are broken. Consistency in enforcing these rules is key so they take them seriously.

- Monitor and communicate: Especially in the beginning, check your child’s phone activity regularly. This isn’t about invading privacy; it’s about protection. Let them know you will be checking – transparency helps maintain trust. When you see something concerning (or something praiseworthy), talk about it. Keep an open line of communication so they’re comfortable reporting problems to you. Many experts say ongoing conversation is the most important safety tool, even more than any app or setting. Make sure they know they won’t “get in trouble” for coming to you if something bad or weird happens online – you’ll solve it together.

- Teach critical skills (pause, protect, etc.): Invest time in teaching the “critical skills” we outlined earlier. Show them how to block numbers, how to report inappropriate content, how to pause before responding. Perhaps practice what to do if they get a mean message or a stranger contacts them. Essentially, train them to be their own first line of defense. This builds their confidence and competence in handling issues.

- Supervise phone use in stages: In the early days, you might have the phone used only in common areas (not alone in their bedroom) and collected at night. As they get older and prove trustworthy, you can loosen some restrictions, but still keep some oversight. For instance, even with a teen, you might still use a filter on the browser or have occasional talks about their online friendships. Stay involved. Parental oversight doesn’t end the minute they turn 13 or 14 – it evolves, but your interest in their digital life should remain.

- Model good behavior: Kids learn by example. Show your child how to use a phone safely by demonstrating it yourself. Don’t overshare on social media, don’t text while driving (absolutely!), and follow the same device-free rules during family times. If you model balance and healthy phone habits, your child is more likely to do the same.

Despite all precautions, understand that completely “safe” doesn’t exist – the goal is to minimize risk and have a plan for issues. If something concerning happens (and eventually something will, even if minor), treat it as a learning opportunity. Work with your child on how to handle it and how to avoid it next time. When kids know you’ve got their back, they’re more likely to come to you and thus stay safer. By combining tech tools, house rules, and open communication, you create a safety net that covers different angles and grows along with your child’s abilities.

Q5: Do I need to use parental control apps, and for how long?

Parental controls are strongly recommended at the start, but they don’t replace parental guidance. Use them as a helper, not a cure-all. A good strategy is to start with tight controls and then adjust over time as your child matures and earns trust. For a 9–12-year-old’s first phone, you would typically: restrict app downloads, filter web content, set daily time limits or “downtime” (phone turns off at night), and enable features like location tracking or approval for new contacts. These controls can prevent many accidents (like stumbling on porn or chatting with strangers) and reinforce the rules you’ve set.

However, you should also explain to your child that these controls are in place for their safety and learning, not because you don’t trust them. As they demonstrate responsible use, you can gradually relax some settings – for example, extending their time limit, or allowing more websites – with the understanding that they maintain good habits. The goal is that by the time they’re older teens, they won’t need heavy controls because they’ll have internalized safe behavior.

There’s no fixed age to remove controls; it depends on the child. Some parents keep certain filters on until 16–17; others might remove app restrictions by 15 but keep an eye on screen time. Keep at least minimal safety nets for as long as you feel it’s necessary. And even when you lift many controls, continue to spot-check and discuss their online life. Remember, parental control tools can be outsmarted – clever kids find YouTube at school or use a friend’s phone. So never assume the controls mean you can ignore what they’re doing. One UK tech expert noted, “you can’t put your feet up and think: my work here is done. ...They’re not perfect – children can bypass them if they’re clever enough”. In essence: Yes, use parental controls (they’re very helpful), but don’t rely on them alone. Their purpose is to assist, while you continue teaching your child how to use technology safely. Over time, the aim is for your teen to self-regulate without needing an app to block them – but getting to that point is a gradual process. Until then, think of parental controls as like training wheels on a bike – you’ll take them off when you’re confident your child can ride safely on their own.

Q6: Should I start with a basic phone or smartwatch instead of a smartphone?

If you have any doubts about readiness, a basic device can be a brilliant first step. In fact, giving a kid a pared-down phone or a smartwatch is a popular strategy to ease into phone ownership. These devices allow the child to call and text (so you achieve the safety and convenience aspect of being reachable) without the many risks of a smartphone. For example, a simple flip phone usually has no internet browser, no social media, and limited features – it’s hard to get in serious trouble on such a device. Many experts and organizations encourage this approach: “Options like these may be a better fit at younger ages,” says the American Academy of Pediatrics, referring to basic phones and watches as alternatives. Similarly, digital safety groups often list kids’ GPS watches or talk/text-only phones as good “training” devices.

Advantages of starting basic: your child learns phone etiquette (like answering your calls, keeping the device charged, not losing it) and gains some independence, while you avoid exposing them to app addiction, social media, and internet hazards too soon. It also helps solve the “everyone has something” issue – your child won’t feel completely left out if they have at least some device, even if it’s not a full smartphone. You can always upgrade to a smartphone later when they’ve proven they can handle it.

Some parents worry a basic phone will make their kid a target of teasing (e.g. “haha you have a ‘dumb phone’”). In practice, many tweens think the flip phones are kind of cool or retro. Regardless, you can explain that every family is different, and this is a stepping stone. You might be surprised – sometimes kids are actually relieved to have a simpler device because it’s less pressure (no social media drama to keep up with).

If you go the smartwatch route, devices like the Gabb Watch or other carrier kid watches are built for this very scenario – they limit contacts to parent-approved numbers and have GPS for your peace of mind. If you go with a flip phone, just prepare that texting might be clunky (multi-tap keys), but that’s okay for basic use. Another creative option, as mentioned earlier, is giving them an old smartphone with no SIM card (Wi-Fi only). They can use it at home under supervision, but it’s not a true mobile phone until you add service.

In summary, yes – starting with a basic communication device is often a smart move if your child is on the younger side or you’re not fully confident in their readiness. It can serve as a trial run. You can say, “This is your starter phone. We’ll see how you handle it for a year, then consider a smartphone in the future.” If they handle the basic phone well – they keep it safe, use it appropriately, and follow your rules – it builds trust that will carry over when it’s smartphone time.

Q7: What rules should I set for my child’s first phone?

You’ll want to set rules covering usage times, allowed content, privacy, and behavior. Here are some common rules that many families include in their phone contracts for tweens:

- When and where: Define “phone-free” times and zones. For example, “No phone use after 8:30 PM” (and have a charging station outside the bedroom), “No phones at the dinner table,” and “Phone stays off during school except if needed to call home.” Also, if your child participates in activities, make sure they know any rules of those places (many schools ban phones in class). Setting these expectations early prevents power struggles later.

- Screen time limits: You might set a daily limit, e.g. “No more than 1 hour of recreational screen time on the phone per day on school days”. This can be enforced by tech (Screen Time settings) and by trust. Make sure they also prioritize homework, chores, and offline play before screen entertainment.

- Apps and downloads: Clearly state that “you must get permission before installing any new app or game”. This helps you vet what they use. You might even restrict the phone so only you can add apps via a password. Also, no in-app purchases without asking – to avoid surprise charges.

- Content and websites: If you allow web browsing or YouTube, lay out what’s off-limits (by category or specific sites). “No using incognito mode, no visiting sites with adult content, and absolutely no viewing porn or violent videos.” You can phrase it age-appropriately, but be clear. Encourage them to stick to a whitelist of sites/apps you approve, especially at first. And, “If you’re not sure if something is appropriate, ask a parent.”

- Privacy and sharing: “Do not share personal information (full name, address, school, phone number) online with people you don’t know in real life.” Also, “Never send pictures of yourself, our family, or our home to strangers.” For older tweens/teens: “Never send or post inappropriate photos – no nudity, no sexual texts – these can have serious consequences.” It’s worth explicitly mentioning sexting is strictly forbidden, as even 12–13 year olds should know that can be illegal when minors are involved. Another privacy rule: “Don’t take photos or videos of others without permission, and don’t post someone else’s picture without asking them.”

- Communication and behavior: “Treat others with respect. No mean texts, no cyberbullying. If you wouldn’t say it to someone’s face, don’t text or post it.” Also, “Do not use the phone to prank call, spread gossip, or cheat in school.” Set an expectation of kindness and integrity online. And include “If you receive bullying messages or something makes you uncomfortable, tell us immediately – you will not be in trouble for speaking up.”

- Safety and strangers: “Never answer calls or texts from numbers you don’t recognize. Never agree to meet someone you met online without parents involved. Be cautious about clicking links in messages; if unsure, ask us.” Essentially reiterate those safety skills.

- Transparency with parents: “At any time, Mom or Dad can look at your phone – and you will hand it over without complaint. You will share your passwords with us and not change them without permission. This is not to invade your privacy; it’s to keep you safe.” Also, “If you make a mistake or something bad happens, let us know. We promise to listen and help, not immediately punish.” This clause is important for maintaining trust and ensuring your child doesn’t hide issues.

- Physical care: “You are responsible for not losing or damaging the phone. Use a case, handle it gently, and keep it in the agreed places. If it gets lost or broken due to negligence, you may lose the privilege or need to help pay for repairs.” This teaches respecting property.

- Consequences: Clearly outline what happens if rules are broken. For example, “First minor infraction: warning. Repeated infractions or major violation: phone is taken away for X days.” Keep consequences proportionate and enforceable. The child should know you mean business but also that they have chances to improve.

When setting rules, use positive framing too. It’s not just about what they can’t do, but what they should strive to do: “Use your phone in ways you’d be proud to tell us about. Remember it’s a tool, not a toy – it’s okay to have fun with it, but it also comes with responsibilities.”

Once you have your set of rules, go over them together and have your child sign the agreement. This formalizes it and gives them a sense of ownership. And don’t forget to review and update the rules as your child gets older. The rules for a 12-year-old’s phone might look different from a 16-year-old’s, gradually shifting from more restrictions to more trust and self-management.

Q8: How can I help my child build good habits and not become phone-addicted?

This is a big concern for parents, but there are strategies to encourage a healthy relationship with technology from the start. Here’s how you can help your child (and whole family) build good digital habits:

- Set a schedule and stick to routines: Children thrive on routine. Establish early on when phone use is allowed and when it isn’t. For instance, maybe they can have 30 minutes after school and again after dinner (if homework is done). By having defined “tech time” and “no tech time,” you help them learn to enjoy the phone in moderation and also enjoy screen-free time. Ensure there’s a consistent bedtime cutoff so the phone doesn’t encroach on sleep (e.g. all devices out of bedrooms by 9 PM). Good sleep and device addiction tend to be at odds, so protecting sleep is huge for preventing dependence.

- Encourage a variety of activities: Make sure your child’s life remains balanced. Encourage plenty of offline fun – sports, hobbies, reading books, playing outside, art, etc. If they have a rich array of interests, the phone is less likely to consume all their attention. Some families set a rule like “screen time earned by outdoor time or chores” to incentivize balance. Also prioritize family activities (game nights, outings) where phones are put away. This shows them that real-life experiences are as rewarding as digital ones.

- Use apps/tools to manage usage if needed: There are features and apps that can help limit addiction – for example, use Apple or Android’s Screen Time settings to set daily limits on particularly addictive apps (like games or YouTube). You can also schedule “Downtime” where the phone locks most apps during homework or at night. These tools can be training wheels until your child can self-regulate. Explain that these aren’t punishments but are there to help them establish healthy habits (even adults use app timers to curb doomscrolling!).

- Teach mindfulness and self-checks: Talk to your child about how to recognize when they’ve had too much screen time – maybe their eyes hurt or they’re feeling anxious. Encourage them to take breaks on their own. One idea is the “pause and reflect” approach: if they find themselves just scrolling or checking the phone repeatedly with no purpose, they should put it down and do something else. Some families implement “Tech-Free zones” at home (like no phones in bedrooms or at the dinner table) so that there are built-in breaks from devices.

- Model and practice: Again, your behavior sets the tone. If you don’t want your child addicted to their phone, demonstrate moderation yourself. Have “unplugged” hours where the whole family, including parents, put phones away. Show them that life goes on without a phone in hand. Also share with them how you manage your own screen time (e.g. “I set my own 1-hour limit for Facebook because I focus better without it”). This normalizes the idea of controlling tech, not letting tech control you.

- Address problems early: If you notice signs of unhealthy dependency – for example, they get very anxious without the phone, or they’ve drastically cut back on other activities – intervene sooner rather than later. Maybe scale back the phone usage or temporarily remove a particularly addictive app. Discuss openly what you observe: “I’ve noticed you haven’t played LEGO or gone biking at all since you got the phone. Let’s find a better balance.” It might be worth a “digital detox” weekend or setting new rules to recalibrate their habits. According to a Pew focus group, even parents acknowledge if they themselves struggle with overuse, it’s unreasonable to expect a 9-year-old to self-regulate without guidance.

Ultimately, building good habits is about creating an environment where the phone is just one part of life, not the center of life. By setting boundaries, promoting other interests, and being a role model, you guide your child to view the phone as a useful tool and source of occasional fun – not as an object that controls them or defines their self-worth. Remember the phrase: “tech is a tool, not a toy.” Reinforce that idea often, and your child will be more likely to internalize it.

Conclusion: It’s About Digital Readiness, Not Just Age

Handing your child their first phone can feel daunting, but it’s also an opportunity – a chance to mentor them into the digital world and instill values that will last a lifetime. As we’ve explored, the question “Is my child ready for a phone?” is really about “Have we prepared our child to use this tool wisely?” Digital readiness is the true goal. That means raising a child who is not only tech-savvy but also responsible, kind, and safe online.

In this guide, we emphasized that readiness hinges on maturity and skills, not a birthday. We broke down phone readiness into emotional, social, and digital maturity, and provided concrete signs to evaluate. We discussed ages and saw that while many kids get phones by middle school, there’s nothing wrong with waiting longer if needed – and indeed, many benefits to waiting until competence catches up with curiosity. We outlined skills like Pause, Protect, Spot, and Decide, which form a foundation for smart digital citizenship. We also made the case that while parental control tools are helpful, they can’t replace the internal controls your child develops through guidance and practice.

Perhaps most importantly, we detailed how to prepare: through conversations, gradual exposure, clear rules, and ongoing support. By investing time in a 30-day plan or a checklist-driven process, you turn the first phone from a leap of faith into a well-supported journey. Instead of tossing them the keys and saying “good luck,” you’re in the passenger seat coaching them through each turn.

As you wrap up this guide and consider your own child, keep in mind a few philosophical truths:

- Every child and family is unique. Try not to compare too much with what others are doing. You know your child best. Trust that knowledge as you set the pace for them. Whether your neighbor’s 9-year-old has an iPhone or your niece didn’t get one until 15 shouldn’t dictate your choice – your child’s readiness and your values should.

- “Not yet” is a perfectly valid answer. If after deliberation you feel your 9–12-year-old isn’t ready, that’s okay. You’re not being “mean” or “old-fashioned” – you’re being thoughtful. It’s easier to delay a phone than to deal with fallout from giving it too soon. And waiting doesn’t mean ignoring technology; it means preparing in the meantime so that when you do say yes, it’s a positive experience.

- Focus on connection and guidance. A phone can either drive a wedge between parent and child (if it becomes a source of conflict or secrecy) or it can be another avenue of connection (if you use it to bond, learn together, and communicate). Strive for the latter. Keep the relationship stronger than the pull of the screen. If you maintain trust and open dialogue, you will always be your child’s go-to “app” for help and comfort.

- Model the digital adult you want them to become. Children learn by watching how we, the parents, handle our devices. Show them that people come first, phones second. Demonstrate restraint, courtesy, and purpose in your own tech usage. This “do as I do” lesson sinks in over time.

In the end, giving your child a phone is not about a piece of technology; it’s about initiating them into a new realm of independence and responsibility. It’s one part of the larger goal of raising a good human being in the digital era. By prioritizing readiness over peer pressure, and education over restriction, you help your child develop the most important software of all – good judgment and values.

When the day comes that you finally say, “Yes, here is your first phone,” you won’t be doing so with fear. Instead, you’ll have confidence in your child’s readiness and in the relationship you’ve built. You’ll know that they understand the privilege and responsibility that comes with that phone. And you’ll continue to walk alongside them as they navigate this new terrain, gradually letting go as they prove their capability.

Digital readiness is the true goal – and it’s a goal you and your child can absolutely achieve together. With preparation, patience, and open communication, your child’s first phone can be a positive milestone that empowers them and brings you closer, rather than something to dread. Here’s to raising a generation of mindful, respectful, and digitally resilient kids!